From Theory to Reality: Case Studies in Sustainable Weight Loss

Two Journeys Through the Three Phases of Energy Emergency

In the last article, I discussed the perpetual and inevitable failure of the calories-in-calories-out (CICO) model and its fatal flaw, in that it does not account for the role of evolution and adaptive responses of the human metabolism. The article covered how these adaptive responses to any energy emergency occur in three phases – the emergency phase, the adaption phase and the reset phase – and how grasping the body’s aims within these phases allow us to perfectly predict any individual’s trajectory, understand what we are seeing and achieve healthy and sustainable weight loss. Without restricting intake.

I feel that the principles laid out in this article are self-evident, although offering opposition against ideas that have become entrenched is not something that can be handled without extensive discussion. Keeping this long article from getting even longer meant leaving aside some case histories, which I think are especially useful for two reasons:

Case histories show these concepts in action, demonstrating how the exact details can vary depending on the person but how the principles remain universal

They underscore how a journey towards sustainable weight loss is exactly that – a journey – and how it is never a case of simply running ‘better’ testing and formulating a more ‘advanced’ plan or deploying the ‘right’ diet, then standing back to admire the results

First, a quick reminder of the three phases of Energy Emergency:

1. The Emergency Phase. In this phase, the body mobilizes energy reserves in order to meet the emergency need, while reducing metabolic rate (investment in non-survival tasks, including any healing tasks). This phase normally sees weight loss occur for several weeks, before downregulation of adrenaline receptors results in a proportionate drop in release of energy from reserves, leading to the familiar ‘stalemate’ where individuals find themselves consuming low calories, experiencing all the symptoms of reduced energy investment yet losing no further weight.

2. The Compensation Phase. The body enters this phase as soon as it has access to a ‘normal’ energy intake. In this phase, it will do what it perceives as necessary to better adapt for the next time it faces starvation (and a pillaging of its energy stores) by doing everything it can to increase the amount of energy it has in reserves. This means maintaining the reduced metabolic rate (and, thus, investment in healing tasks) in order to prioritize adding more energy into storage (ie. weight gain).

3. The Reset Phase. After several weeks of having its energy requirements met, the system accepts that there is no further risk of starvation and, thus, there is no further benefit to either a) limiting investment into non-survival tasks or b) maintaining increased energy in reserve. As a consequence, we see a reliable pattern whereby metabolic patterns improve (most notably in regards to investment in digestion, immunity and healing processes, alongside higher body temperatures and improvements in mood and focus) and the excess energy held in storage is ‘given up’ as there is no further need for it. This is where individuals see ‘spontaneous’ weight loss, without making any changes to their diet or exercise.

Now let’s see how these concepts translate to real-world journeys, considering the cases of both Chloe and Scarlett. I have selected these cases because, although no two journeys are exactly alike, they speak to the need to consider multiple challenges – in both body and mind – and the need to overcome different bottlenecks as they moved through each phase. Equally, the most common patterns to encounter are punctuated by a) a challenge in ‘coming down’ from a high state of activation (and the impact this has on both energy usage and internal state) and b) ensuring that, instead of just eating more and hoping for the best, there is always a need to ensure that mitochondrial performance is attended to (and therefore that the improved energy availability is reflected in the cells).

Chloe - Background & Assessment

Chloe was in her mid-40s. She had a busy schedule that involved part-time work and full-time mothering, but also maintained regular gym visits (at least 5 session per week, split between cardio and weight training). She was aware of being a highly anxious child but felt physically great as a young adult, only seeing hints of issues with her metabolism in her late 20s. This was the first time that she had noticed resistance to losing weight, having previously found that cutting calories would always be reliable in shifting any unwanted weight. It no longer did the job and this was when she had joined the gym, increasing the frequency and intensity of workouts until she eventually saw some movement on the scales (although this still left her well short of her target weight, which she found especially disappointing given the effort she was putting in).

She had maintained this heavy exercise schedule since but found that she needed to progressively cut calories in order to avoid weight gain. In these years since doing so, she had begun to experience hormonal challenges (feeling especially low premenstrually and experiencing major period pain), but had only ever been offered SSRIs to help her mood (a lamentable example of the failures of modern medicine, but unfortunately very common). She also began to experience headaches, rashes and brain fog. After pressing for further investigation, her GP eventually ran a thyroid panel, which showed Hashimotos Thyroiditis (which is where the immune system produces antibodies against thyroid tissue, limiting the formation of thyroid hormone and generating a hypothyroid state). Chloe felt relief at this diagnosis, as it provided an explanation as to the challenges that she’d experienced for so many years.

However, like many, she noticed very little when introducing the thyroxine medication. This prompted her to investigate this deeper and a quest to find a doctor willing to prescribe T3, the active thyroid hormone. This was no mean feat but, when she eventually got her hands on this ‘magic bullet’, she was once again disappointed with the impact it had (or lack thereof).

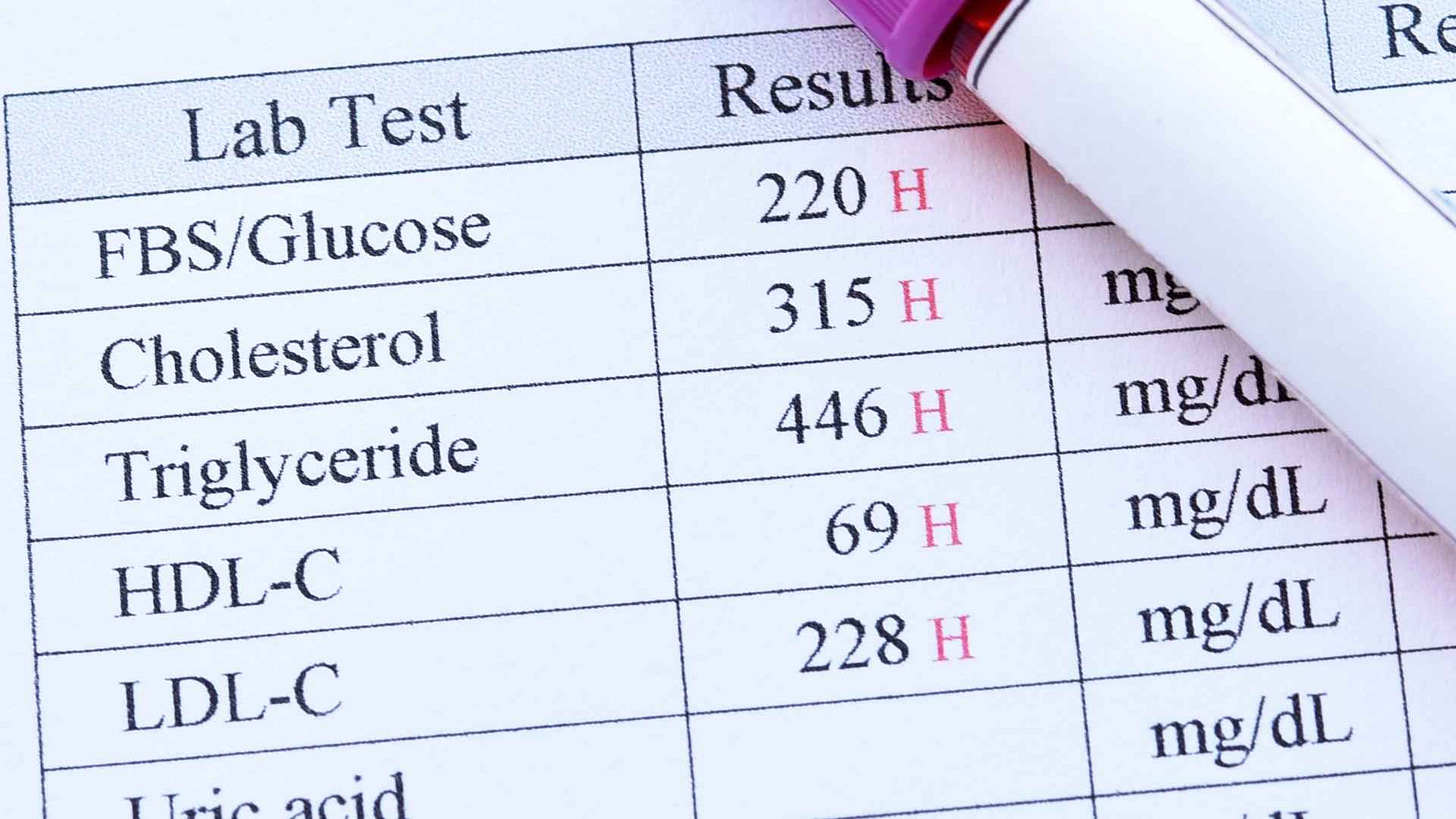

Our initial appointment quickly revealed why this was the case. Her Organic Acids Test showed a number of challenges, most notably raised Malic Acid. This is always very relevant when individuals are resistant to weight loss; it is an indication of low cellular activity of thyroid hormones (often dubbed ‘cellular hypothyroidism’). It occurs due to reduced uptake of thyroid hormones at receptors, a response deliberately deployed by body to lower metabolic rate when energy is scarce. And energy was scarce; Chloe had not measured her caloric intake for a while but, after assessing what she ate on a normal day and the portion sizes, I roughly calculated her intake at only 800 kcals per day.

It was clear that her system was deep in the second of the three phases of energy emergency, that of Adaption. It had deliberately downregulated her energy output, doing so to such an extent that she did not lose any weight at such a low intake. In other words, her metabolic rate was running only ~800 kcals per day (rather than the 1,900+ that we would expect in optimal circumstances).

This ‘economy mode’ is not controlled solely by thyroid activity, as the autonomic nervous system also plays a key role in reducing any heat production not necessary for survival; accordingly, we saw signs of nervous system shutdown in the form of her Heart Rate Variability (HRV) figures, which came in between 60-70 rMSSD (indicative of a mixed-type nervous system response, with both the classic sympathetic and parasympathetic stress responses both active); part of her system was launching the ‘fight-and-flight’-type response in an attempt to dump enough energy into circulation while other parts where trying to deploy the ‘freeze’-type response to shut down energy output during this sustained energy shortage.

This nervous system response is often dubbed ‘functional freeze’ and it is the most common to see when energy intake has been low for a long period of time. In these circumstances, we normally see the HRV figures shoot up for some time once the individual gets enough calories (and no longer needs to scramble for extra resources, thus no longer obligated to deploy the ‘fight-and-flight’ and therefore free to action the energy-saving ‘freeze’-type response to permit the gradual restocking of cellular reserves), before a gradual withdrawal of this parasympathetic stress sees the HRV figures progressively drop in line with these cellular stores being restocked.

As always, it wasn’t caused by just one thing; although the lack of incoming calories was clearly the most profound factor in Chloe’s low metabolic rate, there were also other obstacles in energy metabolism that needed attention. Her Organic Acids Test showed raised Aconitic Acid (a sign of poor oxygen availability in the mitochondria, and discussed in my previous article on the Everest Effect). It also showed low B1 and Carnitine (needed to efficiently metabolize carbohydrates and fats, respectively).

Mitochondrial blockages are relevant because this is what determines cellular energy status, and cellular energy status is what the nervous system is measuring when it regulates energy usage. Such calculations are driven mainly by the hypothalamus, which continuously asks ‘how much energy do I have?’ and ‘how much energy do I need?’ and launches a suitable shift in physiology in response (something we dub ‘the stress response’). It is relevant that the cellular ATP status – the amount of ‘human’ energy available in cells – is always the pivotal factor in these calculations. In other words, we don’t just need to eat enough, we also need to sufficiently convert this food energy into human energy.

Aims and First Steps

Correcting the shortages of B1 and Carnitine were simple (B1 and Carnitine supplementation). So too initial steps to support oxygen usage in the cells (which focused on lowering the activation of the stress response, with both lifestyle changes and adrenal support, ie. Licorice Root).

Getting sufficient calories was not as simple. Although simple in theory, it is relevant that 1. disturbed conditions in the digestive tract can easily result in reduced appetite, and 2. adrenaline is a potent appetite suppressant. In other words, when we have had a sustained period of disinvestment due to low caloric intake, we see two major obstacles that make it very difficult to simply ‘eat more’.

This is a very common challenge to encounter. That being said, it is normally quite straightforward to overcome: eating only a bit more (consistently) means a bit more investment in the gut and a bit less disturbance here. It also means a bit less adrenaline, carving out a window where we can eat slightly more again. This means further, incremental drops in intestinal disturbances and adrenaline, and opportunities to increase calories further. Most people find that they will hit their target intake after 3 weeks or so.

However, many individuals will have to overcome another, more profound challenge. I refer here to the change in inner conditions that occurs when someone has been stuck in a sympathetic state for a long period of time. We had already discussed how Chloe had spent her entire life in a state of ‘fight-and-flight’, so much so that she had never considered herself stressed (something that is naturally very difficult to do when this is the only state they have experienced, thus there is no contrast to make any comparisons).

Put another way, Chloe had never experienced an inner state not dominated by adrenaline. Some will find immense relief when they finally transition into this ‘post-marathon mode’ after being in a state of sympathetic stress for a long period of time, but many others – especially those who have been in this ‘fight-or-flight’ state since their early years, and thus know nothing else – may find the adjustment turbulent.

When we first spoke, Chloe’s system was attempting to deploy the parasympathetic stress response (‘freeze’) but was still subject to major competition from her sympathetic stress response (‘fight-and—flight’), leaving her in this halfway house (as seen in her HRV readings of 60-70 rMSSD). Eating more and using the B1/Carnitine allowed her system enough energy availability that, for the first time in a long time, there was no longer a need for such strong sympathetic activity to scramble for energy resources. Adrenaline dropped and, with this, she entered a more ‘complete’ parasympathetic state (with readings varying between 90-120 rMSSD).

Chloe’s Major Hurdle: Moving Out of the Emergency Phase

Although there are multiple downsides to high adrenaline output (such as disinvestment in digestion and various healing tasks, and inhibition of various pro-cognitive and pro-social circuitry), this hormone liberates energy from storage, enhances alertness and provides a numbing effect (all clearly useful in battle situations). So, just like characters in war films that come off the battlefield only to then notice that they’ve been seriously wounded, we can get hit with waves of sensation (and emotions that they generate) after adrenaline drops. Chloe saw a disappearance of many physical symptoms – headaches and rashes were gone – but experienced feeling much more emotional (to the point that this interfered with her performance at work). But she was able to adjust to being in a non-emergency state, making use of a series of Conscious Connected Breathwork sessions to do so.

However, it’s fair to say that she was caught off-guard by how challenging this aspect of the transition was; we have all grown up immersed by the Western medicine model of one-pill-for-every-ill and I needed to outline how the idea that the sort of shifts required to reboot her metabolism would never be a case of identifying the ‘right protocol’ and then pat ourselves on the back. There is no possible way that the human metabolism can go from the emergency phase of an energy emergency (the first of three phases) straight into the reset phase (the third and last phase). It has to move through the second phase, the adaption phase, and this means ending the acute emergency. This cannot be done without profound changes in the distribution and usage of energy throughout the entire body, and this will always include impacts at the nervous system.

This movement through the phases of energy emergency also meant that she was subject to the distress of weight gain. Although most recognise the obvious need to provide a sense of energy security (and how evolution would ensure checks-and-balances to ensure that energy is now used freely until it such security is achieved), it is nonetheless typical for this temporary weight gain to cause concern. Although temporary, this phase is vital in generating ‘proof’ for the nervous system that the acute energy emergency is over, and the topping up of these reserves is necessary to stimulate a rise in leptin. This is itself key in signalling to the nervous system that adaption has occurred and, as a consequence, that there is no need for further adaption (which sees the body shift into the next and final stage, Reset).

Like many others before her, Chloe experienced substantial conflict at this stage and, although I had warned her about the perils of ‘hedging’ – eating almost enough, but not enough – she tried cutting her calories on a number of occasions. She found that, if she cut her calories down to 1300-1400 per day, she would not experience a return of the headaches and rashes but would continue to experience weight gain. If she cut the calories beneath 1000 per day, weight gain would stop but at the cost of the physical symptoms returning. When they returned, they felt more emphatic than previously (as is normally the case, when we have had an opportunity to experience life without them).

Victory: Transitioning to the Adaption Phase, then Reset

After several rounds of trialling these ‘alternative’ routes, Chloe went all in. She noticed that most of her clothes no longer fit, which was especially disturbing. However, after around three weeks of hitting nearly 2,000 kcals per day, she stopped noticing any weight gain. She had gained around 2kg during the months of variable calories and another 1.6kg in the three weeks of going all in.

From this point on, her journey became much less turbulent. As expected, she saw the expected ‘mobilization’ process play out; as the weeks passed and her nervous system became more settled, her energy security improved. This was further enhanced with tactical support for mitochondrial function, which focused on copper/iron status, steps to enhance oxygen usage (Cordyceps and red light). Her HRV dropped during this time and, although there was a phase when she noticed lighter sleep, we used further breathwork sessions (as well as a referral out for a run of IFS/Internal Family Systems sessions) to allow orientation to this state. When her HRV hit the low 30s, she lost the 3.6kg she had gained during the early phases of the adaption phase.

She was still not happy with her weight but, in line with the ‘textbook’ expectations (and alongside some anti-viral support, followed by further anti-bacterial steps to improve her intestinal microbiome) she then saw a gradual drop into a true parasympathetic state (‘rest-and-digest); 12 weeks after she hit 60 rMSSD, she began to see fat ‘melt away’ despite making no changes to her diet or exercise.

Scarlett - Background & Assessment

Scarlett was also in her 40s and working long hours. She ran a consultancy company which required a lot of her time (to appease both the clients and the unpredictable issues thrown up when running a team of staff). She recalled no issues as a child/teenager and had felt largely ‘unstoppable’ throughout her early adult years, with a natural aptitude for most activities she chose to engage in. It was not unusual for her to wake at 4.30am for a gruelling session with her personal trainer, and then work through until 10pm.

However, after having her second child 8 years prior, she noticed that she just couldn’t keep up this pace. She also never lost the baby weight, as had been the case first time round (and it was noticeable that this was now stored disproportionately, beneath the arms and around the hips/buttocks, which was not the case before). She had re-arranged the schedule in order to counter her lower energy but, once both children were sleeping through the night, she was surprised and disappointed that her previous zeal had not returned. This is when she began taking steps to address her energy and weight.

This initially involved a low-carbohydrate diet and engaging the services of a personal trainer to help her push through in the gym. However, she felt a crushing fatigue after each workout, enough to impact on her ability to concentrate at work, and so moved her workouts to after work. However, this affected her sleep. She took some sensible advice to measure her adrenal output (using the Adrenal Stress Profile, a four-point salivary test) and this showed low cortisol activity.

Cortisol is essential to managing the body’s resources and responses during times of heightened energy requirements (aka heightened stress), and post-exercise malaise is just one of many patterns we see when cortisol activity is insufficient. Others include fatigue, brain fog, lowered tolerance of stress, low blood pressure, dizziness upon standing, salt cravings, frequent urination, feeling slow to wake up in the morning and switch off at night, a drop in energy mid-afternoon before getting a ‘second wind’ in the evening, joint pain, feeling awful if not eating regularly, unrefreshing sleep and (in menstruating women) hormonal imbalances.

Scarlett showed almost all these patterns, with painful periods an issue that had become increasingly prominent. We can see all kinds of hormonal imbalances in these circumstances, although the most common is one that is often labelled as ‘estrogen dominance’. Two main factors are behind this:

1. Endotoxemia and a downregulation of one of the main estrogen receptors (estrogen receptor alpha). Although physical disturbances at the gut lining are relevant, the most powerful influence on this pattern is an excessive sympathetic stress response; this is where the brain senses a mismatch between the energy resources available and the energy resources required and, in response, activates the sympathetic nervous system. This goes on to liberate energy from storage as well as reduce investment in non-emergency tasks but, crucially, it also opens up channels in the gut lining. This is great to grab extra sugars and salts, but also lets in little fragments of dead bacteria (endotoxins) that can cause inflammation and also downregulate hormonal receptors (notably cortisol and estrogen receptor alpha).

This receptor is the dominant form at the hypothalamus, which naturally now receives less estrogen signal. As we might imagine, it then increases its requests for estrogen production to balance things out, and we see high levels of estrogen in the bloodstream. At the hypothalamus, we are seeing a sense of balance; half the sensitivity but twice the hormones to compensate.

However, estrogen receptor beta is still as sensitive as usual and this means twice the action. Because this form of the receptor is found in high concentrations at the amygdala (tasked with emotional signalling), endometrial lining (where it stimulates growth of tissue) and fat cells beneath the arms and around the hips/buttocks (where it triggers increased uptake of energy into storage here).

2. Low progesterone. Stress responses, as we might expect, aim to provide the body with the higher cortisol that it requires to handle such stress. This means increasing the activity of the enzymes that form cortisol (the net result being a ‘theft’ from the progesterone reservoir, a phenomenon often called the ‘progesterone steal’). Stress is a reliable factor in driving down progesterone levels as well as inhibiting ovulation (necessary for the increase in progesterone that should occur in the luteal phase of the cycle), which means there is less progesterone to oppose the effects of estrogen, which is already imbalanced.

For this reason, reducing stress on her system (aka reducing the gap between the energy resources available and the energy resources required) stood out as a priority. In line with 80% of individuals I see who have been ‘treatment-resistant’, Scarlett’s test showed the ‘Everest Effect’ (where low energy production left her system needing to action a strong stress response in order to rustle up the necessary resources, with this stress response causing dysregulated inflammation, poor cortisol responses and impaired oxygen usage, with such issues driving further rounds of stress response). This meant enhancing energy production/oxygen usage at the mitochondria, calming overactive alarm centres in her nervous system and supporting cortisol activity.

Scarlett came in with Heart Rate Variability figures that averaged 22 rMSSD (highly sympathetic) but she too did not feel stressed. Alongside this, her Organic Acids showed key patterns:

Markers for mould exposure and dysbiosis (yeast and bacteria)

High HVA-to-VMA ratio (indicative of reduced conversion of dopamine into norepinephrine due to slow enzyme activity, itself driven by either low copper status and or mould /clostridia metabolites, or both)

Raised 5-HIAA (indicative of increased activity of key immune cells, either platelets or mast cells)

Markers for low B12 and B2

Raised aconitic acid (indicative of reduced oxygen availability at the mitochondria)

Initial Shift from Emergency Phase to Adaption Phase

I naturally focused on the caloric intake, and Scarlett was surprised when she totted up her daily intake on an app; she was eating only 1200 kcals per day. She immediately increased this to 1,800kcals per day.

We also took steps to support dopamine. This neurotransmitter is lauded for its impact on mood and motivation – and it does indeed have these effects – but it’s impacts on muscular relaxation can be pivotal in regards to conditions in the digestive tract (relaxation of the smooth muscles that supply blood to the gut lining turn out to be a massive factor in the oxygen delivery seen by the cells here; oxygen metabolism is often a rate-limiting factor in intestinal permeability – aka ‘leaky gut’ – which can drive systemic inflammation). In Scarlett’s case, we tended to the disturbances in the enzymatic conversion that impacted on dopamine and this involved limiting Clostridia metabolism with Turkey Tail mushrooms, while compensating for the unwanted build-up (and, thus, unwanted oxidation) of dopamine with Green Tea, Rhodiola and Lithium Orotate.

Of course, the B12 and B2 were also relevant, and we provided a B complex alongside additional B2 and Hydroxocobalamin (a particular form of B12). While B2’s role in energy production is direct (it permits entry of fats into the mitochondria for usage and also enhances activity at the electron transport chain), Hydroxocobalamin’s impacts are both direct and indirect; B12 is necessary for optimal mitochondrial function but it also neutralizes a chemical called nitric oxide (which can build up in states of both inflammation and oxidative stress, and prone to driving self-perpetuating cycles of oxidative stress and inflammation that impair mitochondrial performance).

Scarlett quickly shifted into a parasympathetic state (the expected ‘post-marathon mode’), recording HRV readings around 85-100 rMSSD. Unlike Chloe, she found this a very welcome climb-down from being so switched on. However, what she did not appreciate was the weight gain. “I can take feeling slow, it’s actually quite nice, but I cannot take the weight gain.” She had quickly put on 2.5kg and plateaued here.

I had outlined to Scarlett the temporary nature of this weight gain, and how we always see these journeys play out in predictable circumstances:

We end the first phase of energy emergency (‘Emergency Phase’) through both providing the energy and ensuring that the right mitochondrial support is provided (so that this ‘food’ energy can be converted into ‘human’ energy, where it stocks up cellular supplies and allows the nervous system recognizes its newfound supply of improved resources)

In doing so, we allow the system to enter the second phase of this energy emergency (‘Adaption Phase’) and undertake the tasks that our system have determined to be necessary, namely to top up energy in both cells and in storage

When sufficient storage has been actioned and this improved energy security has been maintained for a length of time, we see the system come out of this ‘economy mode’ and begin to make use of its energy supply again. This is the third phase of energy emergency (‘Reset Phase’) and tends to play out in a reliably two-step process in real life; first, we see the nervous system withdraw the parasympathetic stress response that was blocking the mobilization of resources, and with it a modest drop in weight, and then see the nervous system withdraw the sympathetic stress response (which is where the more extensive and permanent weight loss occurs)

Scarlett’s Challenge: Transitioning from the Adaption Phase to Reset Phase

In Scarlett’s case, she had clearly transitioned into this Adaption Phase but she was not seeing any changes in how she was feeling, nor in her HRV readings. All the signs told us the same thing; her system was no longer needing to elicit the emergency response to make ends meet, but we were not seeing any signs of improved energy security. As in, there was no signs that her body was restocking cellular energy stores. This pointed to either a) a lack of energy formation and/or b) increased theft of these resources (by either activated immune cells, in the case of chronic infection, or excessive stress responses).

The factor that stood out most here was mycotoxins (aka mould toxins). In taking her case history, it was clear that she had sustained exposure at a previous property but an inspection of her home found that there was a substantial mould growth beneath the sink of her kitchen. She had this remediated and we introduced binders (Chitosan). However, even after eight weeks after the resolution and the introduction of the binders, we had seen little change in how she felt or in HRV measurements. Anti-viral steps made a difference to some symptoms (puffiness, sleep quality, general motivation) but had little impact on the big picture. I suggested that we look deeper into factors that may influence energy production (especially oxygen management).

Mould exposure is a dual insult to the body in that it is well-characterized as driving inflammation but also impairs function at blood vessels that need to bring blood (and therefore oxygen) to the cells, doing so indirectly but also through increasing coagulation (clotting). We discussed how the ketogenic diet could be helpful in these scenarios but so too steps to handle hypercoagulation. We discussed her options here, and she elected to trial the ketogenic diet while undertaking a blood test for hypercoagulation. When we spoke in our next call, wherein we discussed the test results, she was gushing about the effects of the ketogenic diet: “My brain WORKS again! I feel NORMAL for the first time in ages!”

There are plenty of individuals who see no benefit from the ketogenic diet and some that encounter challenges. However, should there be issues with insulin sensitivity, slowdowns in glucose usage or impaired function at the first step at the electron transfer chain (the ‘conveyor belt’ for energy compounds) in the mitochondria, this change of fuelling can work wonders. But, as noted above, also see disproportionate benefits when there is disturbed oxygen delivery; at just 2.0nmol/L, which is very much in the normal range we will see on a ketogenic diet, ketones have been shown to enhance blood flow to the brain by 39%.

I was expecting to see a massive shift in Scarlett’s HRV values – we don’t see this ‘switching on’ of the brain unless there is a switching on across various pathways and circuits of the body and brain – and, sure enough, her readings had veered dramatically downwards (now 30-38 rMSSD). This meant that we could also now expect the limited-but-measurable correction in weight, although this does not always happen if the cellular machinery is subject to limitations. In other words, the nervous system shifts guarantee a change in the permission given and so we now get to see if the cellular response keep pace with this. In Scarlett’s case, her cellular machinery was operating well and took this opportunity.

Reaching the finish line

She also found that, as well as feeling more comfortable with her body composition, she was now able to work out again. This was valuable for her, as she had always loved attending kickboxing classes (or, more accurately, she had always loved how strong she felt after leaving these sessions).

Scarlett found that she never felt ‘right’ on the occasions that she ate a carbohydrate-based diet and so avoided doing so whenever possible (easily done on normal days, not so much at weddings etc). However, she acknowledged that this was a sure sign that there was still some work to be done rather than a case of carbs just ‘not being suitable for her’.

Scarlett did not initially see the ongoing transition into the parasympathetic state that we had desired, even though she continued to find breathwork sessions extremely valuable (and translated into her work, where she found herself with a ‘strange’ sense of clarity, even in high-pressure situations). However, the recent tests had shown clear signs of hypercoagulation and so this became our focus. I recommended a combination of White Willow Bark (to inhibit the production of thromboxane, an initial step in the coagulatory process), Quercetin (to limit formation of fibrin, the protein that forms the ‘sludge), Nattokinase (to break down existing fibrin) and the addition of Green Tea/Garlic to her diet (to permit her own breakdown fibrin breakdown to take place at a healthier fashion).

She noticed little immediate response in the first week of adding this support (as I would expect, as it plays out over time) but her trajectory changed from this point. I was also curious about the potential role of adhesions; her second child had been born under emergency C-section, a process that regularly leaves adhesions, and adhesions anywhere in the body often create a ‘pull’ on the fascia that can cause all sorts of problems elsewhere in the body (with a common finding being disturbed posture and, as a result, reduced blood delivery into the brain). It was impossible to know if this was playing a role for Scarlett, as pregnancy is itself a huge stressor and so too the sleepness nights that come alongside welcoming a baby into the world (exaggerated when there are now two babies to attend to).

In short, its entirely feasible that the issues she back to notice at this stage were unrelated to adhesions in her fascia. But my thinking was that we could be entirely certain she was human (and this had been the case for several decades); pretty much all humans benefit from removing knots in their fascia, but those who show disturbances in blood flow to the brain tend to show disproportionate benefits).

I therefore suggested some Visceral Manipulation sessions. They had massive effects. The therapist found a number of adhesions from old injuries, but centred in on substantial adhesions from the C-section; this was impacting on the sigmoid colon. As with many intestinal issues - the nerves here have very different behaviour to nerves elsewhere – Scarlett had not detected any intestinal issues but she certainly noticed the difference after this release; visiting the toilet each morning now felt “glorious”.

In solving this remaining issue, we were also given clarity on why she had experienced these challenges. The impact of the stress response (the ‘Everest Effect’), mycotoxins, hypercoagulation and postural challenges had all conspired to leave her nervous system without sufficient oxygen. Having now restored this oxygen supply, we then saw a clear shift into the ‘promised land’ of a true parasympathetic state and she too saw the expected pattern (around 3 months after hitting 60 rMSSD, she began to notice ‘effortless’ weight loss). She now feels strong/energetic and also eats well, yet remains entirely happy with her weight for the first time in many years.

Summary

We live in a world inundated with promises of easy, quick weight loss. None of them work. And we all know they don’t work. But the emotive nature of weight loss (and what this means for us) leaves most consumers unable to walk away from the table, just in case the next hand proves to be the win they’ve been waiting for (and hey, this argument put forward by this doctor on Instagram for Green Coffee Bean Extract does sound quite compelling… what if it works?)

It’s fair to say that sustainable weight loss is actually simple. It’s just not easy. And the last 20 years has shown that, with zero exceptions, there have been some universal patterns:

It has called for achieving energy security (which moves us into the Reset Phase), itself always calling for both sufficient energy intake and sufficient conversion of this energy from ‘food form’ to ‘human form’ in the mitochondria

Supplements were always needed, but these were to generate the platform for change rather than inducing it directly

The biggest changes were always unappealing (eg. eating more, putting punishing workouts on pause) and fell into the category of ‘having to go down to go up’

Most individuals will understandably be surprised when I make recommendations that appear to have no connection to weight loss (be that posture, dopamine activity, somatic therapies, etc)

To this extent, this process reminds me of the old adage that ‘everyone is a salesperson, whether they realise it or not’. And while this has applied to almost every health journey I have co-piloted, outlining the steps required for sustainable weight loss always casts me in the role of salesperson; selling the idea of nourishing the body with sufficient intake and tolerating the short-term weight gain that is necessary (and yes, it is always necessary).

This is where the nervous system work (be this breathwork, or other somatic approaches) have been a central part of this process, both directly and indirectly. Directly in that these steps help to calm overactive alarm centres (which would otherwise induce a need for high energy resources, aka more resources than we have, aka a continued energy emergency) and also in permitting the acceptance required to see the process through; this is, by definition, an emotional response and this is why we cannot simply choose to be more accepting (yet can see profound liberation when we take the rewiring steps that are called for). However, we can choose to take the steps necessary to rewire these reflex responses, in doing so giving ourselves a fair chance of success.

Ultimately, two decades of working with many individuals who ‘cannot lose weight no matter what’ show me that the human body will never choose to store weight unless it deems it an important insurance policy (to guard against the risk of starvation). Take away any signals that deem starvation a risk – that is, take the steps required to provide energy security - and the body will do the rest. The steps required to achieve this are not always what we think they are and they are often the exact opposite of what we want to hear, but evolution sets the rules here. Our job is to follow them.

Next Steps

If this resonates with your experience, the next step is determining exactly where your system is stuck and what sequence of interventions will work for YOUR specific challenges.

1. Get an Organic Acids Test and work on the results with your existing practitioner. My newly-launched Lucid Labs project offers a range of functional tests, including the Organic Acids Test discussed in this article, and includes a personalised interpretation in the list price. This is a urinary test that you take at home and measures over 50 markers across different zones of the metabolism, which include the mitochondrial energy pathways. Find it for the US here and the UK here.

2. Work with me. I work with a limited number of clients one-on-one to:

Identify your where you are at in the Three Phases discussed above, and how much of this is determined by your intake and how much by your mitochondrial activity

Create a personalized protocol that creates energy security, rather than sustains an energy emergency

Guide you through each stage, so you know when you are on track (or not) and don't waste months on the wrong approaches

If you're ready to stop guessing and start with a clear roadmap based on your actual physiology, book a 15-minute call here to see if this approach is right for you.